Learn how Landesa and its partners are building an equitable, sustainable, and secure world.

Reducing

Poverty

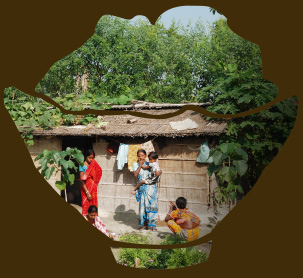

Budhubari, a young widow with three young children, didn't see how she could possibly earn enough money to feed her children and pay their school fees.

Her neighbor showed her the way.

The neighbor, a Community Resource Person (CRP) trained through a partnership between Landesa and the government of Odisha, helped Budhubari apply for legal ownership over the government land she and her husband had farmed.

As a landowner, Budhubari gained access to government agricultural extension services such as agricultural training and subsidized seeds. Now, her two acres of beans, papaya, and corn fill her cooking pot and the excess, sold at market, pays school fees.

"When food was a daily struggle, education for my children was next to impossible," Budhubari explains. "Now, I don't have to worry about the future of my children anymore."

Landesa designed and piloted the innovative CRP model to help the state government quickly and efficiently grant title to landless families who have lived on and cultivated government land for years. More than 80,000 families have already benefited.

Drawn from the same remote rural communities they serve, CRP's act as a bridge between the landless poor and government officials. As trusted neighbors, CRPs are able to identify landless families and provide them with the information and assistance that can change their lives.

Odisha, in partnership with Landesa, is currently expanding the program to reach seven districts, including some of the poorest and most inaccessible areas in the state. Another 300,000 families are expected to benefit.

Empowering

Women

Nareyio Kuyo's remarkable journey began in 2010.

In that year, Kenya adopted a new constitution that promised women unprecedented rights and protections, including the right to own land. But in Nareyio's remote community in the Rift Valley, such rights were little known or understood.

To help ensure that rural women like Nareyio can exercise their new rights, Landesa and USAID launched the Justice Project.

During months of training and dialogue led by Landesa, traditional tribal elders and community leaders in Nareyio's village learned about the new constitution. Over time, the elders and leaders began to see how equal rights for women in their communities enhanced the welfare of the whole community. They developed a code of conduct to ensure women enjoyed equal rights and encouraged women to take a more active role in family and community decisions.

The result: women are finding their voices. They are making decisions, starting businesses, and more than a dozen women, including Nareyio, have been elected to join the community's panel of tribal elders who mediate disputes and often serve as the highest ranking local authority.

"We never had women elders before. Previously, any time a woman attempted to speak out at a public meeting, even if the case involved her own children, she would be ordered to shut up," said Nareyio. "Now women are recognized as human beings. I can have a say in my family. What could make a woman happier?"

Landesa is now advising the Kenyan Ministry of Lands in its ambitious efforts to rewrite the country's outdated land laws and exploring ways to expand the Justice Project.

Reducing Hunger and improving

Nutrition

When Jharna Sarkar's husband disappeared, it was only the beginning of her troubles. Soon after, her in-laws demanded the family house and land for themselves.

Without formal title to her land, Jharna had no choice but to leave. She and her son took up an itinerant life. They eked out a living on the margin's of society, endlessly searching for work that might fill their bellies and provide a way out of their desperate lives.

Then Jharna received title to a micro-plot of land through a partnership between the government of West Bengal and Landesa. Now, on a plot of land about the size of a tennis court, Jharna and her son grow lentils, radishes, leafy vegetables, papayas, pumpkins, and spices such as chili, ginger, and turmeric.

Jharna grows enough food to feed herself and her son, frequently producing enough to share with neighbors and even sell in the market for additional income.

"I have my own place where I can sleep," said Jharna. "It's a good feeling to have a roof above my head."

Across India, more than 450,000 formerly destitute and landless rural families have received micro-plots of land through partnerships between the government and Landesa. The state of West Bengal's micro-plot program has been so successful that it is now the government's flagship poverty alleviation program. Continuing its partnership with Landesa, the state government plans to provide micro-plots to another 100,000 families in the next two years.

Improving

Education

Rakhi lives in an area of West Bengal, India where girls eat last and least. Girls are pulled out of school early to take care of their siblings or married off before they would even be old enough to drive in the U.S.

When she was 15, Rakhi's parents told her they could no longer afford to support her studies and pulled her from school.

Rakhi, a promising and determined student who had just passed the examination to enter high school, found another way.

She enrolled, along with 8,000 girls like her, in Landesa's Security for Girls Through Land Project. The program aims to keep girls like Rakhi in school and reduce their vulnerability to child marriage and trafficking by giving them land-based skills and knowledge of their land rights.

Through the project, Rakhi learned about her rights to own and inherit land and received training in intensive organic gardening skills. With that knowledge, Rakhi planted a kitchen garden on her parents' small plot of land — in an area no bigger than two parking spaces.

By the time she was 17, Rakhi was not only putting food on the table, she was also back in the classroom. The tiny plot, full of spinach and gourds, was feeding her family, paying her school fees, and demonstrating her abilities and value to her parents and wider community.

Rakhi and the other girls in the program are 25% more likely to stay in school.

The project, a partnership between Landesa and the Indian government, is currently expanding to reach more than 35,000 girls over the next year.

Improving

Health

Having suddenly become a widow, Kandhuni Pradhan was determined to take care of herself and her five children.

Then she felt the lump in her throat.

Kandhuni had developed a goiter as a result of her poor diet. However, without formal title to land, proof of residency, or identity documents, she could not access the local government's free medical services and was unable to raise the necessary funds to pay for a doctor's visit. Poor nutrition left her feeling increasingly weak and unable to provide for her family.

To help women like Kandhuni and their families access government services and better provide for their families, Landesa partnered with the state government of Odisha to establish India's first Women's Land Rights Facilitation Center.

The Center's specially trained staff helped Kandhuni obtain a small plot of land to both live on and farm. Equally important, the Center provided Kandhuni with legal documentation of land tenure that allows her to access a host of government services, including: agricultural training, subsidized seeds, desks in the government residential schools for her children, and, critically, free health care.

Kandhuni can now visit a government health clinic for treatment, and her small plot of land is providing her children with a nutritious diet.

This model is being replicated across Odisha. Twenty-three Women Support Centers are already operating. Another 26 are in the works.

Ensure

Environmental Stability

Like most farmers throughout China, Haiyang Wang's life followed the seasons.

There was a season for planting and a season for harvesting.

Every few years there was a particularly destructive season: a time when the village leaders would reallocate land.

Farmland in China is controlled by village collectives. Every three to five years, collectives reallocate land based on updated population figures: families that had gained members would gain land and families who had lost members through migration or death would lose land. Under this practice, fields once farmed by Haiyang's family could become a neighbor's responsibility or visa-versa.

With so much uncertainty over the changing boundaries of his land, Haiyang invested as little as possible into it, growing only what he needed on his family's 10mu (1.6 acre) plot, and without concern for the long-term consequences of his farming practices. But his relationship to the land changed when, as part of historic reforms advised by Landesa, the government ended frequent readjustments, announced that farmers would farm the same plots for 30 year periods, and issued his family a land certificate documenting his 30 year right to farm the land.

With a new sense of security, Haiyang built a greenhouse and began growing high-value vegetables instead of cheap wheat, soy, and corn. His income multiplied and his connection to the land deepened

"The most precious asset of farmers is land and we value it the most," said Haiyang.

Landesa is working to ensure that farmers' rights to their land are protected, ensuring farmers like Haiyang have a stake in the long-term health of their land.

Reducing

Conflict and Instability

When Madaleine Ngezigihe surveys her hillside plot in Northern Rwanda, she looks out on a landscape that has changed dramatically.

"Our community is peaceful because our land disputes are resolved," said Madaleine.

Disputes over the allocation, access, and ownership of land have been a persistent cause of conflicts in rural areas where the majority of Rwanda's population lives. So the government of Rwanda, recognizing the importance of secure land rights, began to focus its attention on the issue.

More than six years ago, Landesa was invited to design a government program that would allow each Rwandan farmer, whether male or female, to obtain legal title to the land they farm.

Tens of thousands of farmers like Madaleine benefited. In Madaleine's village of Kabushinge, farmers also participated in land-related education programs and had gained access to legal aid.

"I have security and hope now that I have a land title because there is nobody who can claim even a tree in my garden — even a single banana tree," said the 70-year-old Madaleine. "If someone tries it, I have evidence. I can take my title to the authorities. I own it. This land is mine."

Our work in Rwanda continues as Landesa designs a dispute resolution project modeled after our work in Kabushinge. This new project enables small farmers throughout Rwanda to learn about their rights, resolve disputes peacefully, and continue to invest in their land and their future.