A version of this article originally appeared in Foreign Affairs.

Why Governments Are Backing Secure Tenure

By Chris Jochnick

In 1967, an article about land reform in Latin America by the law professor Roy Prosterman caught the attention of the U.S. military, which was struggling to support South Vietnam’s faltering government and to keep poor Vietnamese farmers from abandoning their fields to join the Vietcong. Prosterman’s article argued that secure land rights offered farmers a stable path out of poverty and a reason to stay on their plots. In the years that followed, Prosterman (who later founded Landesa, the land rights group I now direct) worked in Vietnam to understand the problems faced by poor farmers and help the government develop a law to address them. Begun in 1970, South Vietnam’s “land to the tiller” law eventually secured land rights for one million Vietnamese farmers. In the areas of South Vietnam where the law was implemented, between 1970 and 1973 , rice production rose by 30 percent, and monthly Vietcong recruitment fell by 80 percent.

In the decades since, dozens of countries have made progress by quietly undertaking similar reforms. Yet many nations still have not gotten around to formalizing the land rights of their citizens: according to the World Bank, only ten percent of the occupied land in rural Africa and 30 percent of the occupied land around the world is legally documented. Moreover, some 1.5 billion people depend on indigenous or community holdings—but only around a fifth of that area is legally recognized. Such gaps contribute to social dysfunction, entrench poverty, provoke conflict, and exacerbate environmental destruction. The good news is that policymakers, businesses, and nongovernmental organizations are increasingly prioritizing land rights in their development agendas.

HARD LANDING

Most people who live in poverty depend on land for their survival. Yet those who lack secure legal rights to own or use that land are not able to protect it from being seized by more powerful interests. This insecurity discourages investment: farmers without secure land rights, for example, often decline to make long-term commitments in the form of better seeds, soil improvements, or irrigation because they know the money they spend on those outlays can be lost if they lose the land. That undermines efforts to boost agricultural productivity and leaves many farmers on the brink of survival. Secure land rights, on the other hand, have been shown to increase agricultural investments and activity. In Ethiopia’s Tigray Region, for example, the economists Stein Holden, Klaus Deininger, and Hosaena Ghebru found that a land certification program led to productivity increases of 40 to 45 percent between 1998 and 2006.

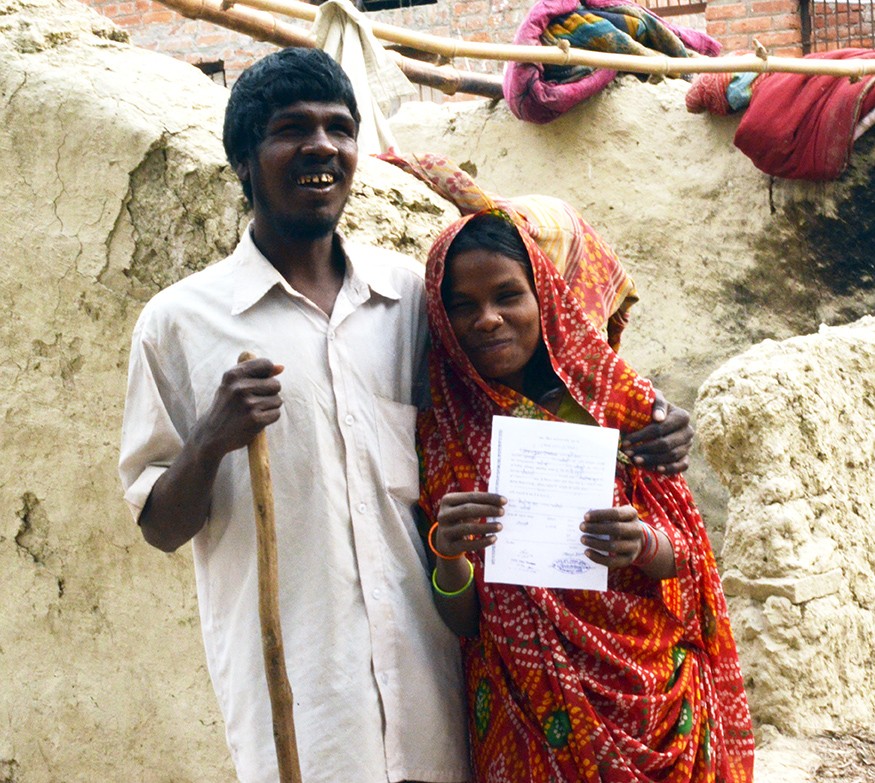

Women in particular can benefit from secure land rights. Today, women in more than half the world’s countries are denied the ability to own, inherit, or manage land by law or custom. Many women in sub-Saharan Africa, where around 60 percent of women in the labor force work in the agricultural sector, can access land only through male relatives. If they are widowed or estranged from their fathers or brothers, they and their children are likely to be left landless or homeless, entrenching their second-class status. A title to even a small piece of land can transform a woman’s social position and economic prospects. That is why the UN Sustainable Development Goals call on governments to strengthen women’s land rights and why major women’s rights organizations, such as Women Deliver, are incorporating demands for land rights into their campaigns. But land rights also produce broader economic benefits. Securing the tenure of small farmers in Japan and South Korea in the decade following World War II helped set the stage for those countries’ strong economic growth in the years that followed. Between 1946, when the Japanese government provided secure land rights to small family farmers, and 1956, Japan’s yearly output of foodstuffs increased by 50 percent.

RIGHTS AND RESILIENCE

People without secure land rights are vulnerable to land grabs by businesses and governments. The Land Matrix, a public monitoring group, has documented more than 1,200 large-scale land acquisitions by foreign entities over the last 16 years, covering around 65 million acres. Because some 93 percent of the concessions granted to investors for commercial activities in emerging economies are already occupied, this dynamic sets the stage for expropriation and violence. In 2015, according to Global Witness, a nongovernmental organization, more than three people were killed each week, on average, defending their land from extractive and other industries. More broadly, population growth, resource extraction, and desertification and flooding caused by climate change are all driving conflict over ever scarcer land in the developing world.

Establishing secure land rights does not only limit conflict over land—it can also help ward off deforestation and climate change. Securing land rights for forest communities is the best defense against deforestation, which endangers the carbon sinks that are essential to fighting climate change. Among individual farmers, insecure land tenure encourages the use of slash-and-burn practices, which has led to large-scale deforestation in the rainforests of Brazil and Indonesia. Climate-friendly agricultural practices can thrive only in places where farmers feel their stakes in their land are secure.

Stronger land rights can also increase communities’ resilience against natural disasters. People without secure rights to their land are more likely to stay put during crises because they fear that they will lose their claims if they evacuate to safety. When a cyclone struck the Indian state of Orissa in 1999, for example, one-third of the approximately 10,000 people who were killed were poor fishermen and their families who refused to leave their homes. Many of those people believed that an official evacuation order was a ploy to evict them. Making matters worse, in the aftermath of natural disasters, the lack of well-documented claims can make rebuilding and resettlement nearly impossible. Five years after Haiti’s 2010 earthquake, for example, some 85,000 people remained in the country’s camps for internally displaced people: many were unable to return to the plots they had informally occupied before the disaster because they had been pushed out by redevelopment and infrastructure projects. In the rapidly urbanizing portions of the developing world, unclear land tenure hampers city planners’ efforts to manage growth sustainably by encouraging illegal and unplanned urban sprawl in informal slums.

GROUNDED

Struggles over land have spurred or exacerbated many of the most devastating wars and refugee flows in recent history, including in Colombia, Myanmar, Rwanda, Sudan, and Syria. For national governments, insecure land rights can create existential threats; for the international community, addressing them is the key to securing peace and managing refugee flows.

The good news is that a growing number of civil society organizations have incorporated land rights into their missions, using new platforms and technologies to scale up their efforts. Land rights are increasingly making headlines, and the Thomson Reuters Foundation has dedicated an entire platform to the subject. Donor governments, multilateral institutions, and private foundations are also beginning to back the land rights agenda, since it often aligns with their other development goals in such areas as food security, health, and economic growth. Three of the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals explicitly call for secure land rights—a sign of the organization’s recognition of land rights as a critical tool for development. Businesses are also getting on board, since the conflicts and land grabs that accompany insecure land tenure threaten firms’ investments and reputations. Some industry groups have voluntarily adopted new standards around land rights, and companies have incorporated respect for land rights into their agreements with suppliers, investors, and governments.

Governments have the most power to make further progress. Dozens of countries have already committed to strengthening indigenous land rights through international accords and constitutional reforms. Countries such as Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda have guaranteed equal land rights for women, and Chinese and Indian authorities have strengthened the land rights of hundreds of millions of farmers. Perhaps nowhere is the recent progress more promising than in Myanmar, where the government is working to secure the land rights of nearly 30 million subsistence farmers. As secure land rights take root elsewhere, the gains they produce will bring prosperity and stability to the world’s poorest populations.

Chris Jochnick is Landesa’s CEO.

Related blogs